Peer out of the window of Becky Allen’s office and you can see into the expansive gardens of Buckingham Palace. It is a reminder of the vast difference between the lives of the few and the very many.

It is a difference that Allen, a one-year teacher, then academic and now director of Education Datalab, which hopes to influence policy with education data, has come to learn, and accept.

While describing her life as “very middle-class” in a large Sussex village, she recognised when she started her studies at the University of Cambridge that there was a whole different world to the one she knew growing up.

“I was not coming from a deprived background, but I lived in a part of Sussex where people didn’t commute into London because it was too far away, so they did ‘normal’ jobs. I wasn’t exposed to this world of movers and shakers, and people who are huge influencers in the society we live in.”

At Cambridge, she says, she found “a completely different group of people”, who were, on average, wealthier, and more worldly-wise. “So many had been to private school, which was a shock for me because I knew that private schools existed . . . but I thought that they were just a kind of . . . oddity.”

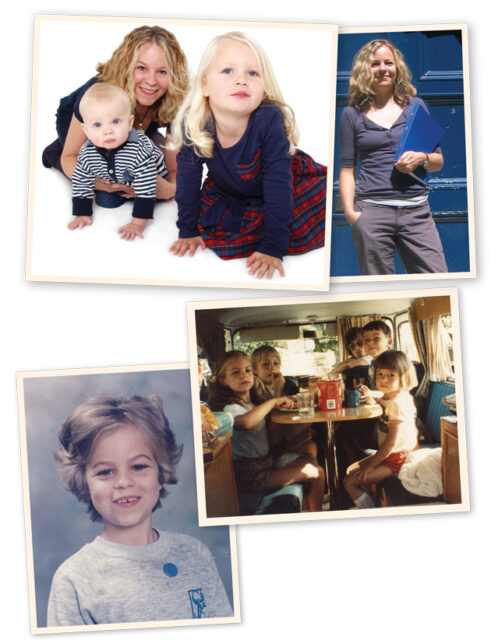

Allen, a middle child with two sisters, remembers a free childhood, in the days before mobile phones, where she would spend time at friends’ houses after school, or taking part in countless extra-curricular activities – violin and piano lessons, drama clubs, choirs.

Her “normal” upbringing has pulled her back to Sussex village life, now in a neighbouring community close to her childhood home, to raise her two young children, four-year-old Juliet, and 11-month-old Eddie.

For someone who has achieved much academically, she admits that she spent most school mornings copying her friends’ homework during registration.

“I’ve never been the type to be particularly interested in conforming or following what people wanted to do – unless I really respected them and I was really motivated and interested by what they were doing.

“So I wouldn’t describe myself as hugely well-behaved in school, and I can imagine that for some teachers I was a complete nightmare!”

Despite this, in 1995 she got a place at Cambridge to study maths. “I took double maths, physics and chemistry [at sixth form]. Two brilliant women who taught physics and chemistry really inspired me, were fantastic role models and were responsible for me doing so well academically.”

I’ve never been the type to be interested in conforming”

But maths wasn’t quite right for her. Her contemporaries “were nearly all men”, she struggled to find people she got on with and she was more interested in politics and society. She switched to economics half-way through her degree.

She was also chair of the University Labour Club during the 1997 general election: “It was really exciting;

you felt like the world was going to change. I had lived almost my whole life under a Tory government, so it was a really incredible time.”

She graduated in 1999 and spent “half a day” at the then Department for Education and Employment to see what kind of job she could do. “I walked out and never went back because I thought, ‘If I work in a place like this, I will just shrivel up and die’.”

Her lack of willingness to conform had come to the fore. She did not want a job where she was expected to leave at 5.30pm; she wanted something that she was so excited about she wanted to stay until it was done.

A brief stint at the think tank IPPR in 1999 was followed by a move to JP Morgan as an equity research analyst later that year. She says the training was “fantastic” – and she travelled the world.

“I’d never really been on a plane, then I was finding myself on one more than once a week. It was just really exciting.”

The skills she learnt – to write concisely, analyse data and use Excel – she still uses today.

A year before she left JP Morgan, the 9/11 terror attacks shook the world.

The emotion of what happened catches Allen off guard. She says she hasn’t thought about it in a long time and her eyes fill with tears.

“It’s stupid to say it, because the people that were affected were my clients – they weren’t me, they weren’t my friends, they weren’t my family – but it does make you re-evaluate what you’re doing in life and why you’re doing it.

“If your life ends tomorrow, will you feel OK with the life you’ve led?”

In 2002, she started her PGCE at the Institute of Education (IOE), training to teach economics and business studies. “There is an immediacy in teaching when you walk into a classroom and you work with children. You can see right there and then that what you’re doing matters.”

In the end she only taught for a year. “I always meant to go back, but the longer you are away, the harder it is to go back.”

The IOE became her professional home for the next 12 years as she completed her masters and PhD, and later became a senior lecturer and then reader.

She has taken two years’ absence to set up the Education Datalab with FFT, the non-profit school data company, saying that it was an “irresistible opportunity”.

“It’s really only the kind of people who are data crunchers that understand the importance of having good data infrastructure around them.”

She hopes to influence education policy and practice through largely quantitative research and describes the past five years of policy as “completely relentless” – she hopes too that there will be a chance for the sector to catch its breath.

“My interests really are still in compulsory schooling, and so we’re working on a whole series of projects, most of which have been funded by external funders, just looking at the different impact of policies that the government has introduced.

“I am particularly interested in school accountability, so a lot of the work I have done has been work on performance indicators and on parental choice on school admissions systems. I am still working on lots of those things still!

“It’s hard to escape the things that you end up knowing a lot about.”

It’s a personal thing

If you could live in any era, which one would you choose and why?

This one, of course. Much as I complain about gender inequalities, well-educated women have greater opportunities to live the life they choose than ever before.

What was your favourite TV show when you

were a child?

We didn’t watch much TV, but I remember watching and loving Pob, Lost in Space and Happy Days at my dad’s house on a Sunday. My children love Octonauts, Bubble Guppies and Peppa Pig.

If you were stranded on a desert island, and you

could have one book and one luxury item, what would each be?

Can I take my laptop with a solar charger and the entire national pupil database on it? If so, then I’d need a decent econometrics reference book such

as Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data by Jeffrey Wooldridge.

What is your morning routine?

I am not instinctively routine orientated or a morning person. My daughter Juliet, on the other hand, has developed an elaborate routine for us to follow that regularly takes two hours and

includes songs from The Jungle Book, Frozen and Bubble Guppies. My son Eddie, adds to the joy of mornings by emptying every drawer and cupboard below waist height.

Tea or coffee?

We are a coffee household. Specifically, Has Bean Coffee’s Blake Espresso Blend. In the office I drink

tea because the coffee isn’t up to scratch.

Curriculum Vitae

Born February 15, 1977

EDUCATION

1982-1988 Steyning Primary School

1988-1995 Steyning Grammar School (comprehensive)

1995-1999 Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Economics and maths

2002 – 2003 PGCE, Institute of Education (IOE)

2004-2005 Masters in educational and social research, IOE

2005-2008 PhD in economics of education, IOE

CAREER

1999 Institute for Public Policy Research, researcher

December 1999 – September 2002 Equity research analyst covering media and cable companies, JP Morgan

2003 – 2004 Economics teacher, Mill Hill County High School, Barnet, north London

2008-2014 Lecturer (later senior lecturer, then reader) in economics of education, IOE

Present director, Education Datalab

Your thoughts