The government want to tackle ‘coasting schools’. Nicky Morgan has described them as schools that may be in “leafy areas” but nevertheless fail to realise the “full potential” of their pupils.

This week the government released the definition they will use to find this sort of school.

Under the proposed law, coasting schools are defined as:

– Until 2018, those that have a low proportion of students getting five GCSEs AND have low progress, then

– After 2018, those that have three years of a low proportion of students making median levels of expected progress

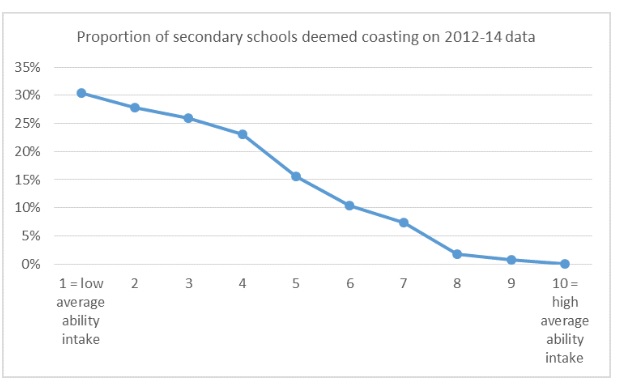

But there’s a problem. As research by Education Datalab has shown, this will disproportionately hit schools with lower ability intakes, which are typically in poorer areas. The government could argue that this is because, somehow, teachers in poorer areas simply have lower expectations than those in richer areas, but it’s a thin argument when presented with these sorts of graphs.

What’s even more odd about the definition is that, for at least the first two years, schools will be measured on pass rates – with protection given to any school where more than 60% of students get five or more GCSEs.

But, why? If coasting schools are those in the “leafy suburbs” with plum intakes then we would entirely expect them to meet this measure and yet still be failing their pupils in terms of progress. THESE are the real coasting schools. Not the ones with poor ability intakes about to be whacked by the new definition.

This tension is what this Labour document from 2008 on coasting schools (yes, really!) set out to resolve.

Click on the image and you can go read the whole thing.

It is weirdly similar to what the Conservatives are trying to do now. Take this section for example:

“Coasting schools are schools whose intake does not fulfil their earlier promise and who could achieve more, where pupils are coming into the school having done well in primary school, then losing momentum and failing to make progress”

That could have come from Nicky Morgan’s latest speech on coasting schools. The classic lines are all there: not fulfiling promise, losing momentum, failing to progress.

It goes on:

“They are not performing badly enough to receive an inadequate judgement from Ofsted, or to risk significant numbers of parents choosing to send their children to another school. Nonetheless they should be achieving better outcomes for their pupils and providing a more exciting and challenging learning experience.”

Besides the bit about ‘exciting’ learning – (I doubt Morgan is bothered about that) – the rest is exactly the same rhetoric we are hearing now about coasting schools.

So where’s the big difference between Labour’s idea and the Conservative one? It’s in the definition.

Labour define coasting schools as those with GCSE scores above a threshold BUT have below average progress. Labour’s plan specifically targets the schools doing well in terms of their GCSE pass rates but whose pupils, having come in with average-to-high ability rates, only come out with Bs or As – rather than A*s.

This compares to the current Conservative definition which specifically protects these sorts of schools by stopping any school above a 60% GCSE pass rate threshold from being considered as ‘coasting’. As datalab’s research shows this helps stop schools in wealthier areas – “the leafy suburbs” – from being hit.

Hmmm.

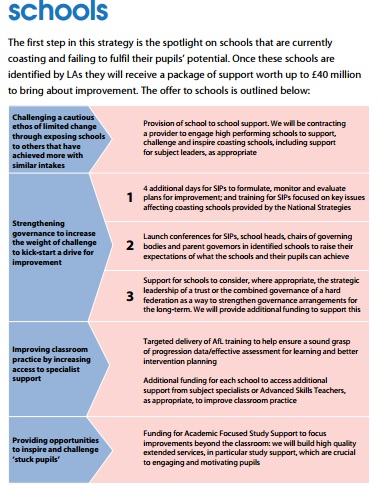

The other difference between Labour’s 2008 idea and the Conservative one now is the ‘package of support’ for coasting schools.

The current offer from Morgan is for ‘national leaders of education’ to help schools in need or, otherwise, make an academy sponsor take over the school’s management.

Labour’s plan is more specific (if slightly management consultant-y):

There is a hint even in this Labour plan that the school leadership might need to change (step 3), but there’s also a focus on teaching (via specialist teachers), a focus on pupils and what will be done to improve their motivation. Elsewhere in the document there are also funding commitments.

What’s most distinctly different to the Conservative situation, though, is the focus on learning not structures. Every improvement strategy clearly refers to an improvement for pupil learning in a way that is completely lost from the current definition of coasting schools. If Morgan wants to sell her plan, she needs to start explaining precisely how NLEs and academisation change the pupil experience; precisely how teaching is going to improve. If she can’t do that, the plan will struggle to convince.

Okay, so the Conservative definition isn’t wonderful for a few years – but isn’t this issue resolved in 2018 when coastings are defined only by a progress measure?

For a while I thought this might be true, but poking around in the evidence it appears that it’s not. The fact is, schools with high-ability intakes appear to progress more quickly than those without. So, while a progress measure is better than a threshold measure, (because it takes into account the fact that children arrive at secondary school with different starting points), it doesn’t take into account the difference in progress rates.

I can see why the government doesn’t want to deal with this uncomfortable fact. One of the only ways to do so would be to write into the law a sort of ‘handicap’ progress rate for poorer kids than richer ones, or kids attending a selective versus non-selective schools – a bit like contextual value added measures used to do. But that’s politically impossible. You can’t write into a law that a poor kid is expected to do less well than a rich one. It’s howl-provoking, defeatist and, actually, quite patronising. But the problem is that if you don’t include it (which the government haven’t), then any progress measure inevitably ends up whacking schools with poorer intakes far more than it whacks those in “leafy suburbs” and hence the entire point of the policy is lost.

This is a bind. And it’s not one I have any solution for. But it seems to me that if you truly want to find the real coasting schools then you wouldn’t begin with a definition, as is currently proposed until 2018, which protects those schools above a certain GCSE threshold. Instead, you would go after schools that have high GCSE pass rates and very low progress rates, just like the Labour plan suggested in 2008.

This whole business of school improvement has become like “Whack a Mole”. This is the fairground game where you hit a mole with a mallet and try to smash it into a hole. As soon as you do so another mole pops up.

In the UK our schools are the moles. But there is a twist. In the fairground game it is possible to smash all the moles into the holes. In the UK education version it is impossible. This is because school improvement measures are now all relative. A school becoming not coasting automatically forces another school in the system to be coasting. As fast as a school makes progress another does not make progress. This is a causal relationship. Success causes failure elsewhere. The system cannot allow all students to achieve their potential. It is impossible by design.

As Headteachers and teachers work harder and harder in one school they make it harder and harder for the next school to achieve success. This is the mad world of educational “whack a mole” where in the end no-one is the winner. This is because the teaching professionals will all drive themselves to ill health, like hamsters running ever faster on a wheel that has no exit door.

If we reduce the outcome, year on year progress, to an equation then it may look something like this:

intake ability x quality of teaching and teachers x leadership x resources x parental engagement = year on year progress (i.e. not coasting and above 60% floor target)

A rather simplistic view of education but then is not the view of the current policy makers. Laid out like this it is easy to see what needs to be changed in order to make progress each year.

In order to make any improvements in the next year, to increase the output from this equation something would have to change. We could add another factor to the left of the equals sign ( + “X”) or change the value of an element in some way.

I have no evidence other than past teaching experience but not all intakes are the same each year. I would argue that the “intake ability” factor fluctuates but this is not taken into account in such a simple model. Hence we need a progress measure but progress of a cohort can not be compared to a national figure of achievement if the local intake profile does not match. The only claim I could see being made here is that all children are equal, there are no differences in ability or in potential but that the school is the limiting factor. In short all those things to the left of the equals sign except the intake. This leads to some simple conclusions.

If students do not make progress it must be the fault of the:

1) teaching

2) leadership

3) resources

4) parents

Now number 4 is out for a number of political reasons so that leaves 1,2 and 3 or in short “the school”. Give the running of the school to somebody else and you solve the problem. We know that when that happens who ever takes over will look at 1 and 2. There may be a nod to #3, resources, it may even be the Trojan hoarse that allows a new host in or the sugar that coats the pill. So the leadership is replaced and the teachers have to work harder of course. It’s mainly their fault anyway, they teach the children after all.

BUT – will any of this make any real difference. Changes only buy time until another change comes along. Unless that is you understand fully the equation and make the changes where they are necessary or have a more realistic and valuable output measure.

I want no child to leave school without recognising their potential, even if they fall short of achieving it. I say this because I, and neither can a school, control all factors in the equation. Learning does not stop after school either and so learners who believe in themselves are more likely to be life long learners.

I believe the equation is rather more complicated anyway – see this article on the learning equations: http://wp.me/p2LphS-3e

If we have numbers 1,2 and 3 of my fault list sorted (the learning environment) then the best place to start is with the first element in the equation, the learner. Carol Dweck would probably start here too. The mindset of the pupil is a significant factor in being a successful learner.

However even with motivated and engaged learners we will reach a plateau after time and whilst we have a “norm” intake and a bell curve to set people against this will always be the case (60 becomes the old 40).

This leaves us with the only alternative we have left if we are to ‘save our school’ (and careers) and that is to make sure we do not have a “norm” intake and that we, year on year, recruit more and more potentially “able” pupils (read engaged parents mostly). This means some schools will have their intake changed too but not for the better as far as they are concerned, the big shiny school down the road has poached any pupils who have engaged and supportive parents and who’s children show potential. There is a limit to this too. So the cycle will start again.

Is there a solution to this problem of a world class education system, well yes there is. Perhaps we are just trying to measure it the wrong way. Perhaps the measure we should be looking for is learner engagement. At this point I will stop, I have written enough already!

More from Advocating Creativity in Education at http://www.4c3d.wordpress.com

This is the reason for a more informed debate about measuring education. A lack of understanding of the different measures available is being used as a smoke screen to cover up the true intentions of a policy.

The DfE know they need not suffer these problems with expected progress, because,,,well,,,they invented Value Added which projects more progress among higher attainers. Therefore they must have chosen not to use Value Added in favour of % expected progress.

The reason can only be that % expected progress selects low attaining and more disadvantaged schools. These happen to be the kind of school that stubbornly remain under local authority control.

This is clearly a cynical policy designed expressly to forcibly convert the last remaining schools under local authority control to convert to academies.

Lack of understanding of expected progress and value added is being exploited by the DfE to disguise what would be a very unpopular policy.