Rebecca Wheater looks at a new PISA 2018 analysis that sheds light on the conditions for disadvantaged pupil’s academic success

Recent national and international evidence has shown that the Covid-19 pandemic has increased the negative impact of disadvantage on educational success. Understanding how to mitigate this is therefore vital to ensuring an equitable recovery for disadvantaged young people.

New NFER research highlights the importance for these students of understanding how you learn and of creating environments where pupils believe their ability will develop over time, rather than something that is fixed.

These findings come from further analysis we undertook of pupils who took part in OECD’s Programme of International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018. Although the data was collected prior to the pandemic, the analysis provides insights into how we can support pupils as they return to school having missed a significant amount of learning.

There were some encouraging findings about how well schools in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are supporting disadvantaged pupils. These included increases in the performance of disadvantaged pupils in reading and maths compared with previous cycles, and stable performance in science against an international overall drop in performance in that subject.

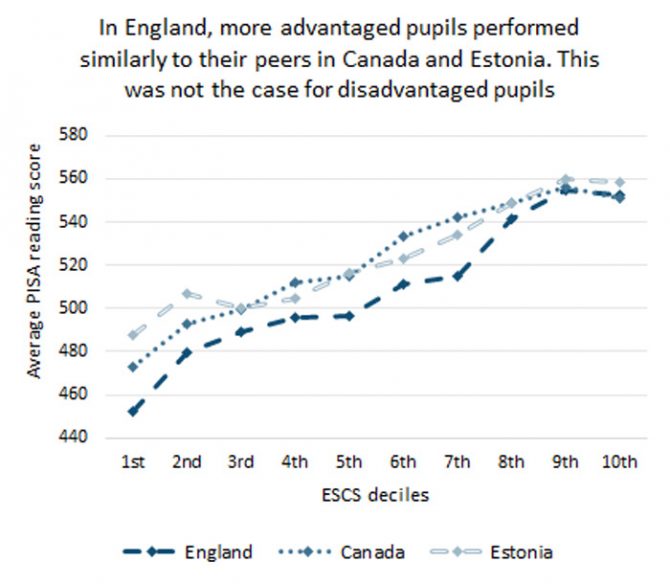

However, disadvantage remains the single most influential factor impacting on educational under-achievement. While no country can claim to have solved the problem, some countries are doing better than others. For instance, England’s most advantaged pupils perform similarly to the most advantaged pupils in Canada and Estonia. Yet these two high-performing countries’ PISA success can be attributed to better performance of their disadvantaged pupils compared with those in England.

In spite of their socio-economic disadvantage, some pupils overcome barriers and attain high scores in PISA. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, around one-third of disadvantaged pupils achieved at a level considered by PISA to equip them for success in later life.

Digging deeper into the PISA data can help us to identify areas for support. NFER’s analysis found that disadvantaged pupils who did well in PISA despite the odds had a better understanding of how they learn – or ‘metacognitive strategies’. They were also less likely to believe that intelligence can’t be changed – to have a ‘growth mindset’. In addition, they had high aspirations for their future education or careers and were less likely to truant.

Supporting metacognition

These findings support previous research findings, such as from the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), that teaching and using metacognitive strategies can help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, pupils who were disadvantaged but high-achieving were more likely to use metacognitive strategies than low-achieving disadvantaged pupils.

As the EEF advises, metacognitive strategies can be taught in conjunction with subject specific content that will help to cement them as transferable skills. Our new findings make a strong case that they should be. The Sutton-Trust/EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit rates metacognition as a high-impact, low-cost approach to improving the attainment of disadvantaged learners. The evidence suggests that use of these strategies can be worth the equivalent of an additional seven months’ progress.

Creating rewarding environments

Resilient pupils were also more likely to have a growth mindset. That is, resilient pupils recognise challenges as external, understanding they can be confronted and tackled. They believe that their efforts at school contribute to their success in school and the future.

Early intervention

Resilient pupils had high aspirations compared with their disadvantaged, low-achieving peers. By 15 years old, pupils should already have a good idea of the general level of jobs and education that are in scope for them. Therefore, any interventions that focus on raising aspirations should start from an earlier age.

As children return to schools, these findings re-emphasise the impact of disadvantage on educational attainment and life chances. But they also indicate which tools and strategies are likely to work best in the recovery effort – intervening early, positively, with a focus on subject knowledge and metacognitive strategies.

I wouldn’t disagree with what Rebecca has written here but let’s not pretend that those with mental health and wellbeing barriers to learning (1 in 5 now) can access all of this without some of those barriers being removed. We know that disadvantaged children especially in deprived areas are likely to have greater barriers to learning and accessing all of what Rebecca describes and we need to address this before we implement high quality teaching. Simplifying disadvantaged as just being further behind underestimates the barriers to learning which we would plan for if a child had a SEND barrier to learning.

Besides the few issues over ‘ disadvantaged ‘ pupils mentioned in this article I think that it is VITAL to look at not only the PISA results in the UK ( before COVID) in 2018 and the published results in December 2019 but previous PISA results, especially from 2010 and the criticisms over the UK’s curriculum / education (which was labelled as ‘stagnated’) and its low academic results in Reading, Maths and Science compared to 78 other countries approximately in 20th place for years for ALL pupils.

The severe criticisms from the ‘ boss ‘ of PISA Andreas Schleicher in 2018 over the narrow curriculum, too much teaching to the test, too much testing, not using teachers expertise and understanding etc is not as severe as the much more worrying criticisms of the high percentage, too high a percentage of children in the UK who are

‘ miserable’, can see ‘ no future’ etc. He hi – lighted the ‘ well being and performance ‘ issues in the UK.

As reported by The Guardian

” Those in the UK had the biggest decline in life satisfaction since its last survey in 2015″ ( 3rd Dec 2019).

Kevin Courtney ( neu. org.uk ) stated

” PISA findings should be a wake up call to to the government that its policies are taking education in England in the wrong direction”.

” PISA finds a clear link between successful education systems and pupils’ sense of belonging and life satisfaction”.

” Education should inspire”.

Accurate work and research needs to be done on the PISA results plus other research etc . GL Assessment for example have made assessments since March 2020 and concluded that children on free school meals do not appear to have been more adversely affected than their peers in the core subjects……..