New research suggests that the government’s flagship 14-19 technical schools have become a dumping ground for lower-ability pupils, raising questions over its plan to allow schools to move pupils based on their ability at 14.

Research published today by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) found pupils at university technical colleges (UTCs) and studio schools were more likely to have lower attainment and to have “under progressed” in primary schools.

There is also evidence that multi-academy trusts with their own 14-19 institutions are moving lower attaining pupils into the vocational schools at higher rates.

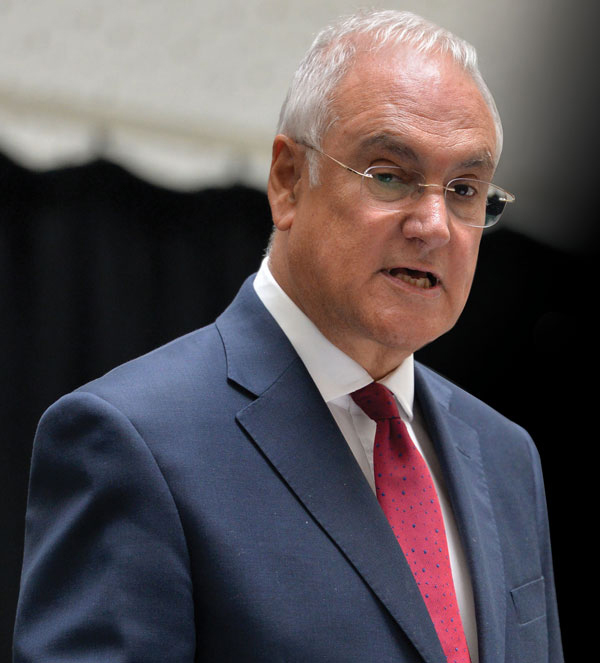

The findings back up concerns about the colleges, with Ofsted chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw warning against the UTCs becoming a “dumping ground for the difficult or disaffected”.

The green paper, published on Monday, outlined proposals for grammar schools to expand only if they met certain conditions, which could include allowing pupils to join selective schools at the ages of 14 and 16, as well as 11.

But Jonathan Clifton, associate director for public services at the IPPR, said the government needed to “better understand” which pupils were enrolling in 14-19 schools.

“This report shows the difficulty of creating distinct academic and vocational tracks in the English school system.

“There is a real danger that vocational institutions become the preserve of those with low prior attainment or from disadvantaged neighbourhoods.”

UTCS and studio schools are integral to education secretary Justine Greening’s plan to push through grammar school reforms that she claims will establish a school system of “diverse education”, with parents able to “find the school for their child that is tailored to their needs”.

The left-wing think tank study, Transitions at age 14, found that 14-19 institutions largely attracted boys (68 per cent, compared with 51 per cent secondary school average).

Pupils transferred to technical schools within the same multi-academy trust were also more likely to have lower prior attainment, compared with pupils joining from a different trust.

The coalition government introduced UTCs and 14-19 free schools to offer, it said, world-class vocational education for pupils from all backgrounds.

But the schools have been beset with problems, such as high closure rates and difficulties recruiting pupils.

Schools Week revealed in March that nearly one in three studio schools had closed (14 of 47).

Last week, it was announced that the planned Burton and South Derbyshire UTC will not open after recruitment problems, despite the government spending £8 million setting it up.

But Olly Newton, director of policy and research at the Edge Foundation, which aims to raise the status of practical and vocational learning, said the report confirmed that 14-19 schools provided an opportunity for pupils who failed to thrive in mainstream education.

He said pupils that achieved GCSE grades below the national average “consistently exceed expectations” in both UTCs and studio schools, which “provides them a pathway to university, an apprenticeship or into a job”.

He explained the low number of girls was largely because both schools attracted a large proportion of students in subjects such as engineering or computer technology – which have large gender disparities nationally.

I think that we really have to stop talking about children who ‘underachieve’ in the ‘mainstream’ system as if they are all incapable of achieving anywhere and therefore needing to be ‘dumped’. If UTCs and Studio Schools are able to offer a different way of learning that brings out children’s abilities (and I have personally seen examples of that), then shouldn’t they be praised as a superior model to the schools that ‘dumped’ them? At the risk of sounding trite, there are – thankfully – many different forms of achievement.

UTCs are a very bad idea. See

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2016/09/09/plastic-intelligence-ebacc-and-the-cognitive-underclass/