Absenteeism has become endemic in our schools. The search for solutions is keeping headteachers awake at night but, despite concerted efforts, absence rates are not improving.

School absence hovered around 4.7 per cent in the years before the pandemic struck, rising to 7.5 per cent last year, according to Department for Education data. But persistent absenteeism – where pupils miss 10 per cent or more classes – has more than doubled, rising from 10.9 per cent in 2018-19, to 22.5 per cent last year.

That equates to 1.6 million pupils, and the number is not going down. Attendance data for this academic year up to March 31 shows the rate was 22.6 per cent.

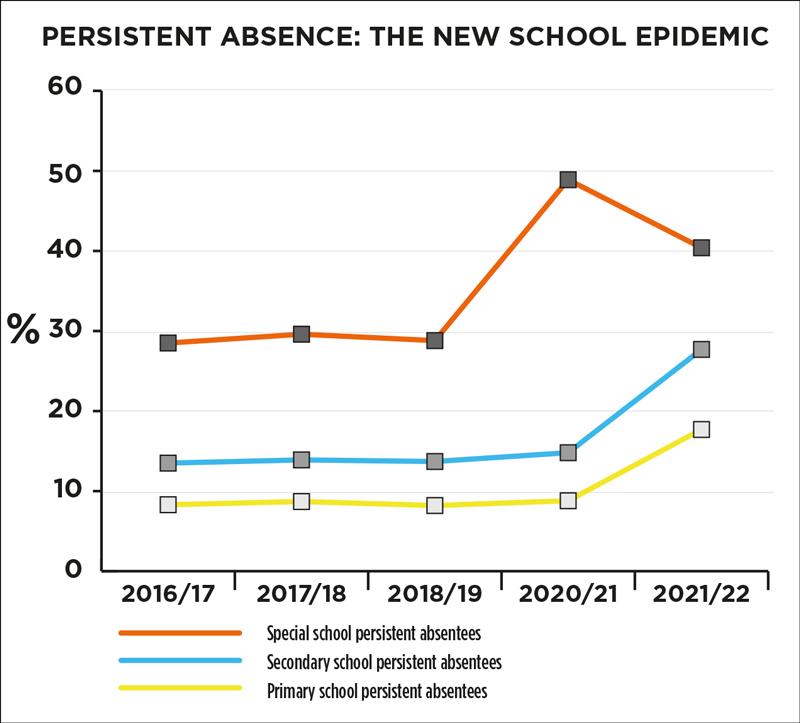

It varies significantly by school. Last year the persistent absentee rate was 17.7 per cent in primaries, 27.7 per cent in secondaries and 40.4 per cent in special schools.

A snapshot of attendance data in April from Arbor, whose management information systems are used by 5,000 schools, shows the youngest and oldest pupils are worst affected. In reception, more than a quarter missed school regularly. At secondary, almost half of year 13s were persistent absentees, compared with just 19 per cent of year 7s.

Poorer pupils and those with SEND are more likely to miss school. For SEND pupils, according to Arbor’s data, the rate was 40 per cent in secondaries, up from 39 per cent in the DfE’s 2021-22 figures.

Special school pupils fared even worse, with almost half persistently absent this year. Arbor’s data also found that gifted and talented children were twice as likely to skip school regularly at secondary (16 per cent) than primary.

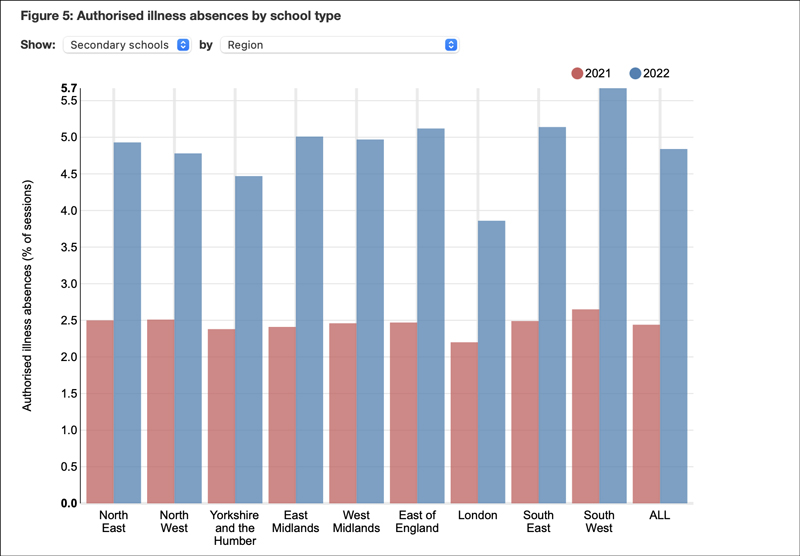

Analysis last week by SchoolDash found rises in absenteeism in every region and type of school, but London schools, those with larger ethnic-minority populations or better Ofsted ratings tended to have smaller increases.

Alice Wilcock, head of education at the Centre for Social Justice centre-right think tank, said absence was “the new epidemic for schools”.

Why are children missing school?

DfE data from last year shows illness absence rose from 2.1 per cent in 2020-21 to 4.4 per cent last year. Unauthorised absences rose from 1.3 per cent to 2.1 per cent in the same period.

SchoolDash managing director Timo Hannay believes there are “more relaxed attitudes among parents in allowing children to stay home”, with a “proven capacity of schools to provide online alternatives to in-person teaching”.

Nearly a quarter of children missed at least one Friday during the autumn 2021 term, a study based on three academy trusts by the children’s commissioner found.

Dame Rachel de Souza told MPs in March this was because many parents now worked from home on that day. “We’ve had evidence from kids, ‘well, mum and dad are at home, stay at home’. We’re seeing slightly different attitudes in the post-Covid world.”

Lee Elliott Major, the University of Exeter’s social mobility professor, and Andy Eyles, of University College London, said some pupils were off due to “crippling anxiety and a loss of social and academic confidence”.

But evidence they submitted to MPs stated other families “appear to have lost their belief that attending school regularly is necessary for their children, with some openly questioning whether a return to schooling is needed”.

Fines are a stick [schools] have been told to beat parents with

A Schools Week investigation last month found about 125,000 children across England – 1.4 per cent of all pupils – were home educated at some point in the last academic year, a 60 per cent rise on pre-pandemic numbers.

The strikes and high teacher absence rates are also believed to have had a detrimental impact on the notion of school being mandatory for all. Wilcock said councils had parents “ringing up saying, ‘how dare you try to fine me for taking my child on holiday when teachers are striking’”.

The cost-of-living crisis means some families cannot afford to supply clean uniform or pay for lunches and bus fares every day. There are also concerns that gaps in NHS provision are exacerbating absenteeism.

An investigation by The House magazine found waiting lists for children to access mental health services had more than doubled in the past five years. Schools in the North East are reporting three-year waiting lists for CAMHS. In Bristol, children must be in “crisis” before referral for an autism diagnosis.

A fine mess to be in

The government has encouraged the use of fines to get children back to school. Councils can fine each parent £60, rising to £120 if not paid within 21 days. Non-payment after 28 days could lead to three months in prison and a fine of £2,500.

In 2021 former education secretary Nadhim Zahawi ordered councils to tell parents that keeping children off had “repercussions”. But some leaders say fines further damage the increasingly fractured relationship between families and schools.

The total number of penalty notices for unauthorised absences plummeted from 333,388 in 2018-19, to 218,235 in 2021-22 – a drop of 35 per cent. While lockdowns account for much of that, Wilcock believes it also reflects a reluctance from councils and heads to use fines post-Covid.

Michael Gove recently suggested that parents who fail to ensure their children attend school regularly could have child benefit payments stopped.

Wayne Harris, deputy head at Washwood Heath MAT’s strategic attendance leader, said fines were a “stick [schools] have been told to beat parents with”.

Publishing school attendance data creates a “pressure cooker environment” which is “not a child-centred approach to supporting families”, he added.

Harris recounts visiting the home – riddled with mould – of two asthmatic children whose parents did not pay their £60 per child fine after taking a “crap” term-time holiday in Cornwall. That had risen to £389 and will go up by another 50 per cent if they do not pay within 14 days.

“Their house is falling to pieces and now they’ve got to find nearly £800. It’s heartbreaking,” Harris said.

Fines can also have unintended consequences. One head told Schools Week he knew of parents who had pulled their children out for home education because “they don’t want to get fined”.

But Christina Jones, CEO at River Tees MAT which operates five academies for vulnerable children, said having a fine “on the table allows you to have more robust discussions with that family”.

Enforcement is a postcode lottery, though. In 2021-22, six councils issued more than 5,000 penalty notices, while three issued none.

And does the approach even work? Luton issued the most fines of any council last year, when its unauthorised absence rate was 2.1 per cent – 70th highest in England. Latest figures show this has tripled to 6.6 per cent – making it the 17th highest rate in the country.

The government plans to introduce national standards that all councils follow to ensure consistency with fines. But councils can still have parents prosecuted without issuing penalties.

Warrington, which did not issue any penalty notices in 2022, instead set agreed nine-week targets for attendance to improve before resorting to legal action. Since last September 160 parents have been given targets, of whom 19 went on to be found guilty in court.

Attendance pressures

There is also concern that schools are submitting an attendance “Code B” intended for when pupils are present at an approved off-site educational activity, when pupils are really working from home.

One secondary head indicated B codes were being used to boost attendance levels, after the department “cut right down on off-rolling and sending kids off on work experience”.

“If you say, ‘we’ve sent work home’, you can be quite unscrupulous. We are under pressure to get attendance stats up, which creates a culture where some exploit the system by doing dubious things.”

There is also concern the government’s expectations are unrealistic, particularly in deprived areas. Glyn Potts, head of Newman College in Oldham, feels he should be “proud” of the school’s 92.8 per cent attendance levels, given its disadvantaged location.

“But the government will say it needs to be 100 per cent. We’re in this vice grip of being held accountable for poor attendance. Doing what we’ve always done will not change some of that ingrained distrust of schools going on out in the community.”

Harris echoes this and fears the top-down focus on data can lead to poor decisions. He recalls two children moved to a hostel after their father almost killed them, and although they were not in school, he wanted them kept on roll “to safeguard them, so we knew where they were”.

But this brought down attendance levels, which was highlighted by Ofsted during an inspection. He asked inspectors: “What do you want me to do – get these children off roll so attendance improves? That’s one element of the pressures we’re facing.”

Tackling the problem

The DfE is setting up attendance hubs for schools to learn from those getting a grip on the problem.

The idea came after Northern Education Trust’s North Shore Academy managed a 94 per cent post-Covid attendance rate, despite being in a deprived area of Stockton-on-Tees.

Michael Robson, the trust’s senior executive principal, said the model involves “boots on the ground”, with up to 5,000 home visits a year providing “support and sometimes challenge – saying to families there is no good reason for absence”.

We’re in this vice grip of being held accountable for poor attendance

It also involves a “brand new pastoral structure, with lots of provision taken in-house”. Wellbeing and educational welfare officers are recruited in every school.

The DfE is understood to have 10 more MATs lined up to establish similar hubs. It recommends that penalty notices are issued where support is unsuccessful, but there appears to be growing aversion to deploying them.

Ellie Costello, director of SquarePeg, a social enterprise for families with attendance issues, said attendance enforcement can come across as “centred in the old-fashioned rounding them up, handcuffing them and chucking them back through the gate”.

She had heard “awful stories of education welfare officers and even headteachers banging on doors, forcing their way into homes, pulling the duvet off kids and shouting at them”.

She added: “We’ve got high proportions of families accused of fabricating and inducing illness and being threatened with child protection proceedings. It’s really problematic.”

Harris is calling for schools to “work with families not against them”. He has created a child-centred attendance practice framework “built on connectedness and belonging” and a network sharing good practice to which 388 schools have signed up.

But Major and Eyles warn that evidence on how to reduce absenteeism is extremely weak, adding: “It is likely there will be huge variation in the effectiveness of schools’ efforts.”

Meanwhile, Jones has an alternative solution, trying to ensure each pupil has at least one positive relationship in school with a peer, which she believes makes their chances of attending much higher.

“Work around internal emotional-based school avoidance is picking up complex issues around the environment in schools. Most children are not attending because they feel school is not a nice place to be.”

My daughter was a confident student in Year 11 when Covid lockdown happened. School work was on her computer and having no social interaction left her confined to her room and looking for social interaction in gaming. Not only did this ruin her academic results, she became a totally different person, one who was mentally difficult to deal with. Thank goodness the school helped once I confessed that she tries to get ready but then has a nervous breakdown. She still has good days and bad, but the damage has been done.

The senior school in our Trust has recently taken a blanket approach to attendance and sent letters out to all parents whose children have less than 85% attendance. This has had a massive negative impact on parents of Send children and those with medical conditions. The school has an attendance policy protocol which they haven’t followed yet seem to believe that arranging Attendance Panel meetings for these parents is acceptable. It’s unlawful and discriminatory and contravenes all the guidance and Laws in place to protect and support these children. The Senco at the school whilst Head of Inclusion has little to do with attendance and has told me herself that’s the case. How can this be right? There is a legal duty on schools to make reasonable adjustments and to work with children and families yet this doesn’t happen and proved by this latest initiative by the school.

Well the strikes are not in any way going to help with absenteeism alongside secondary schools always having half days at the end of term!

In response to comments about strikes not helping, on the contrary, teachers are striking for better funding to keep the staff like pastoral leads, attendance officers or school counsellors, whom we desperately need to help get children in school so the teachers can do their jobs and teach.

Why is this article pushing the motion that we are now ‘post-pandemic’?

I can’t quite believe what I’m reading here. The article contains the answer to it’s own questions. It states that school absence has risen by 2.8%, and that sickness absence has risen by 2.3%. There’s your answer.

Schools are allowing pupils to be routinely infected with Sars-Cov2, a serious pathogen with long lasting damage that we don’t yet fully understand. The science is now overwhelming, with clear data showing mental and physical impacts on children way beyond the acute phase – see here for one example – https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(23)00115-5/fulltext

Instead of trying to offload blame for this onto parents, nebulous ideas of culture changes, or other weak reasons, just start addressing the role classrooms have in spreading covid. Then you’ll see absence rates decline.

I attended secondary school in the 1970’s. Similarly to today, teachers were more interested in their salaries, cars and posing in their clothes. Also a time that we began to embrace endless layers of officials and paper work in these new establishments. I walked away from school angry when I was 15.

How these days have unfortunately returned.