The buzz phrase within education policy and schools over the past six years is to close the gap — between disadvantaged children and their better-off peers; between boys and girls; between white working-class boys and everyone else.

But what impact have policy decisions had on pupils at the top and bottom end of the attainment scale?

Figures put together for Schools Week by the education data analysis group School Dash highlight a worrying trend

Falling levels of achievement by high-attaining pupils appear to be exacerbated by caps on exam results, while the improvement of low-attaining pupils has remained stubbornly low, new data shows.

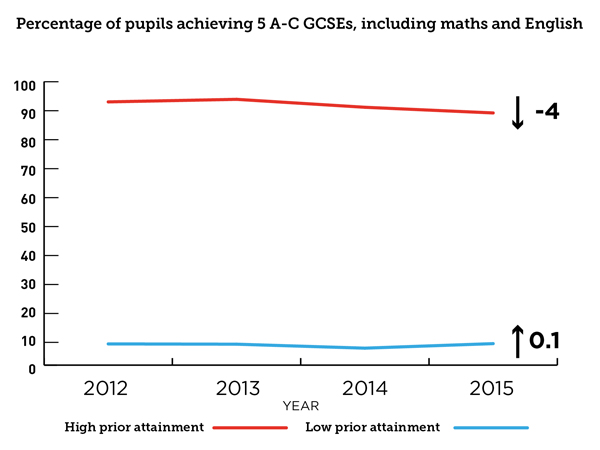

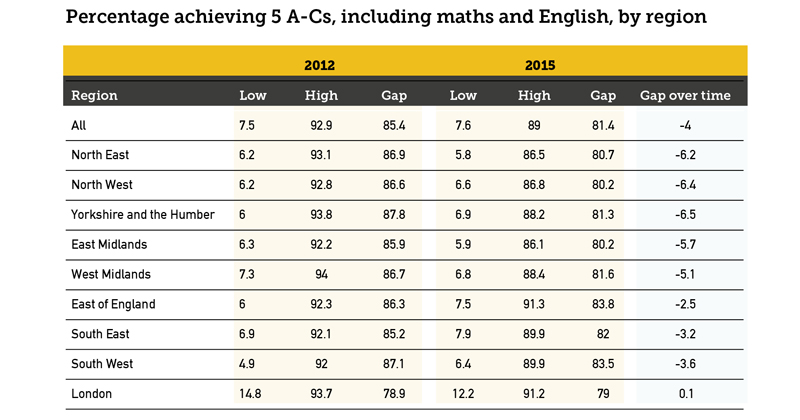

School Dash’s analysis of GCSE results shows the gap between the highest and lowest attaining pupils has closed over the past four years by 4 percentage points.

However, the new figures suggest this has been driven exclusively by a drop in the performance of high attainers, where there has been a 4 percentage point fall since 2012.

Results for pupils classed by the government as “low attaining” have risen by just 0.1 percentage point.

Lee Elliot Major, chief executive of the Sutton Trust and founding trustee of the Education Endowment Foundation, said the figures were a “cause for concern”.

“We need to ensure that all children reach their potential, both the high achievers and those who are low achieving.”

Analysis of 2,800 secondary schools in England discovered that in 2015, the gap between the two groups — those with high and low attainment when starting their GCSEs — was at 81.4 percentage points.

A total of 89 per cent of pupils at the top achieved five A*-C GCSEs including English and maths (5A*C EM) in 2015, while just 7.6 per cent of low-attaining pupils reached that benchmark.

However, in 2012 92.9 per cent of high attainers got 5A*C EM.

Meanwhile, the proportion of low-attaining pupils getting 5A*C EM in the four-year period has increased by just 0.1 percentage point.

One explanation for the dip in the high-attaining pupils’ results is the decision by exam regulator Ofqual to implement “comparable outcomes”.

These, in effect, prevent a large increase in the number of top grades at GCSE. Or, as Michael Gove, former education secretary, described them: “Prevent the erosion of standards.”

But, education consultant Ros McMullen, a former headteacher, says the decision has led to pupils “losing out” and believes this data backs sector concerns about the ability to show school improvement.

“If you have a system that is improving and everybody is doing better, then you will definitely see the pass rates go up, but [Ofqual is] working to keep pass rates the same.

“This is quite dangerous because it means you are working in a zero-sum game; you can’t really see nationally whether schools have improvement or not. All you will see is a redistribution of those grades.

“There was probably some truth in the claim that if pass rates went up year-on-year it meant that standards were getting lower. However, if you work to keep pass rates the same then you are not allowing yourself to see where there has been genuine improvement.”

Leaders and teaching unions have criticised comparable outcomes since their introduction in 2012 in an attempt to clamp down on grade inflation.

An Ofqual spokesperson said the approach means that if pupils taking a qualification are of similar ability to the previous year, then “we would expect the overall results for both cohorts to be similar”.

“Comparable outcomes do not restrict the number of top grades being awarded to able students. Under our approach to monitoring, exam boards have the opportunity to put the case for an award being higher or, for that matter, lower than is predicted.

“The approach also avoids students in the first year of a new qualification being disadvantaged because they are the first to sit new qualifications.”

Elliot Major said the data suggested too many children were still leaving school without basic numeracy and literacy. A clear focus was needed on pupils both at the top and bottom of attainment levels.

“All the evidence highlights two really stark challenges for the education system: ensuring we support and stretch the highest achievers irrespective of the background they come from, but also addressing the lowest attainers.

“If you look at any data, it is incredibly depressing that for all the effort and evidence-led reforms we have had in recent years, a stubborn number of children leave school without basic numeracy and literacy.”

But Dave Thompson, from Education Datalab, warned against drawing too many conclusions from the figures.

He said the attainment bands might not be comparable, particularly for the 2015 results, as some pupils were involved in the 2010 boycott of national primary tests and therefore may not have been assigned to the correct bands — which had quite large regional effects.

Thompson also said last year’s cohort would not have been tested in science at the end of primary school and, as results in that subject were often higher than English

and maths, more may have ended up in the upper band of attainment before 2015.

“But even with the above, the percentage of pupils in the upper band increased from 33.5 per cent in 2012 to 35 per cent in 2015.”

He said with a “static” awarding system, such as comparable outcomes, if pupils were performing better at key stage 2 this would not necessarily lead to an improvement in key stage 4 outcomes. Changes in performance tables also removed multiple entry GCSEs and a large number of vocational qualifications from the measures.

Since 2012, he said, these changes have meant the proportion of children achieving 5A*-Cs (or equivalent) in any subject has fallen from 85 per cent

to 68 per cent last year.

However, Sir Tim Brighouse, former London Schools Commissioner and leader of the London Challenge, backed the view that regulation of grades was having an impact.

“We are bedevilled by a system that is always normatively referencing everything, which doesn’t serve anyone very well. How do we know if the standards are rising or falling?”

He said the best way to assess standards at GCSE was to have randomised

tests, taken by a sample of pupils every year, rather than everyone taking GCSEs.

Brighouse said he wouldn’t want schools to be held accountable for the results but the system would allow “real standards” to be tracked “rather than standards that are understandably affected by the fierce accountability regime on schools”.

In March, Ofqual ran a full-scale trial of the national reference tests for year 11s.

In future about 9,000 pupils will take the tests. The results will be used to decide the proportion of pupils across England able to achieve certain grades in their GCSEs.

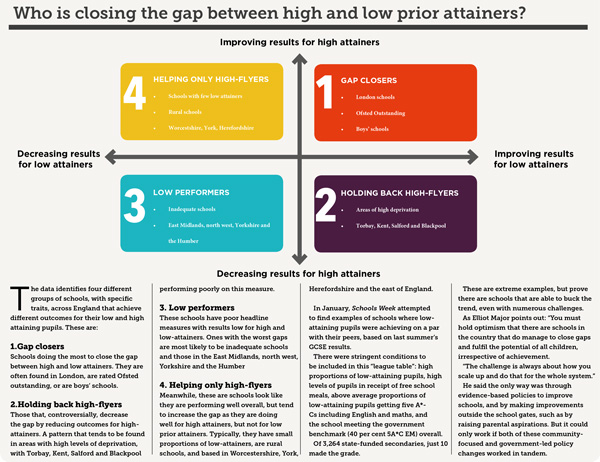

Timo Hannay, School Dash founder, said: “If education is genuinely going to provide opportunity for all then we should pay almost as much attention to the gap between the most able and least able students as we do to absolute levels of attainment.

“This analysis shows that some schools

do well on both fronts. Understanding exactly how and why could help others to replicate their success.”

Brighouse added: “We should not be limiting the achievement of those at the top but raising the standards of those at the lower end to a level that increases their resilience and self-confidence so they can discover their talent, whatever that talent might be, and take it to its fullest extent.

“Don’t close the gap; mind the gap.”

Your thoughts