Steiner schools have a somewhat controversial reputation.

Based on the ideas of Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian occultist who died in 1925, the schools were recently described as “playful and hippyish” in a Newsnight segment – whereas officials in the Department for Education have raised concern that Steiner’s works are racist and anti-Semitic.

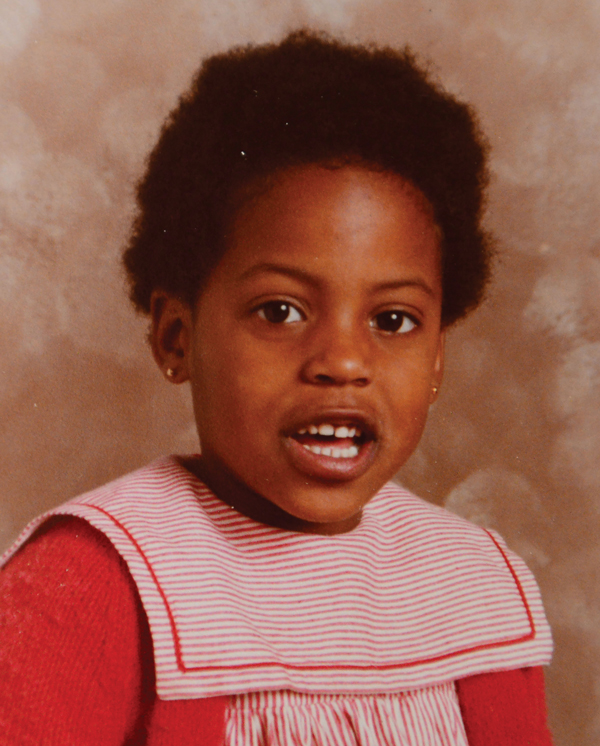

Two things are therefore surprising about today’s interview with Angie Browne, principal of the Steiner Academy in Bristol. The first is that the school exists: it’s one of three taxpayer-funded Steiner schools set up as part of the free school programme. The second is that she is black.

“I don’t really have a view on what Steiner’s view on race might have been; but we’re running a school here using his principles around teaching and learning, not his personal views – if they were indeed his views – on race.”

On the critics who tried to stop the free school from opening she says that she’s “only interested in engaging in the debate as far as it’s about what we’re actually doing in the school”.

She continues: “So far, what the critics have brought don’t bear any resemblance to things we’re actually doing in the school – offering children a really healthy balance of an approach to learning that’s balancing the head, the heart and the hands.”

It’s an upfront, courageous stance and is inspired by her own background.

“I am just awestruck really, by the women in my family,” she says, mentioning her 90-year-old grandmother, a seamstress, who came to England in 1957 from Jamaica.

“She made this incredible journey … and she just worked her whole life … it really moves me. I think it’s incredible. The guts she showed, is something I am beholden to take on.”

Browne’s mother also moved her young family, from London to rural Dartmoor.

“They’re pioneers, the lot of them, they really are. That term resonates for me.”

As a black woman, she is in a minority in school leadership, and just as her parents and grandmother struck out on their own, she wants to open the debate about race and gender in the profession.

I shouldn’t be the only black person in the room

“Schools are heavily dominated by white male headteachers and teachers, and that doesn’t represent our school population. That’s quite startling. There is something about it never being mentioned that becomes an issue in itself, because it’s quite evidently an issue.

“I don’t talk about the fact I’m a black headteacher … I barely talk about being a female headteacher, and the problems and challenges that brings.

“But I am determined, in this role anyway, to talk about it, and if I do one thing for the children I teach or have taught, this might be it. I shouldn’t be the only black person in the room.”

Born in 1975, Browne spent her first 10 years in Finsbury Park, growing up with her mother Sonia, a teacher, her stepfather John – whom she calls “dad” – and her younger sister Melanie. Her stepbrother Jo lived with his mother in Birmingham, but the siblings are close.

Her parents split up when she was two and a half, and she hasn’t seen her biological father, Dwight, since she was eight. She does not know where he went.

“I really loved him, I always wanted to see him, but I never really got to know him. My stepdad, who has always been there, is the person I always refer to as my dad because he’s literally always been there.”

Browne thinks Dwight, who was born in Montserrat, went to live in America, but his family have no contact with him either.

“I spent my teenage years … angsty about wanting to find him, and I see it with children all the time now. How important it is when you’re a teenager to know ‘Why do I feel this way?’”

She turned the anxiety into curiosity and became an enthusiastic learner until she had to move to the Teign Valley, between Exeter and Dartmoor, in her final year of primary school.

What felt like a “terrible move” to 10-year-old, city confident Browne, turned out to be an “amazing” change.

“We were the only black people in the village, and in the school. I don’t remember it being difficult, it was just … I never noticed myself as a black person and then suddenly I was really conscious of being black in a very white, rural school.

“And there was a real evident lack of awareness of not just what black people were or who they might be or where they might come from, but also what London was like.”

She remembers hearing racist comments one day at secondary school but when an older pupil – “Vince” – stepped in, she never had any trouble again.

Losing her bearings during A-levels, she dropped out of college and left home at 17. Browne moved into a shared house, wanting to have fun and socialise. She quickly realised she needed education: “Without the anchor of study, it didn’t feel secure.”

She re-enrolled at college and gained A-levels in English literature, theatre studies and philosophy.

Soon after, Browne moved to Bristol with her then boyfriend, and never left. “I think I always had this plan to go back to London … and got as far as Bristol!”

While working at Venue magazine, based in the city, she began an English degree at University of the West of England (UWE) on the site where the Steiner Academy now sits.

Pointing out of her office window, she says: “My first lecture was in that hall over there, and my first seminar was in that classroom over there! It’s just the most unusual turn of events.”

Encouraged to become a teacher by her aunt, she applied at the last minute to complete a PGCE and became an English teacher for four years before setting up a youth work project for children struggling to stay in mainstream education.

Browne used to walk past an abandoned chocolate factory on her way to her job. She dreamed of setting up a school focusing on the principles developed in her youth work.

“I started to think about what was feeding children’s souls and whether we could add something more wholesome into the mix.”

In her mind, she said, there was a vision of a school but it didn’t exist yet, and she couldn’t figure out how to make it happen: “Which is always a bit annoying really.”

After a spell at a pupil referral service, she became interested in Steiner education and the idea of setting

up a free school. By chance she then saw a job advert

for a principal of Steiner free school, in Bristol. “There was this synergy.”

Being pregnant didn’t slow her down. Inspired by the pioneering ways of her mother and grandmother, Browne applied and was stunned to learn that the school was planned to open in the chocolate factory.

Sadly, the practicalities of removing asbestos put the dream on hold. The school is located instead on the beautiful St Matthias campus, where Browne studied when it was part of the UWE The school opened in September 2014 and now has 187 pupils.

What has it been like opening a school with a young child?

“As a mum, and as a teacher, you never quite feel like you are doing enough – you will never be a good enough mum and you will never be a good enough headteacher.

“It has to be possible to bring life into the world and bring forth the children who are going to school, and to be able to work in a school as well; that shouldn’t be an impossible task for a woman.”

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What book would you take to a desert island?

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, Alice Walker’s curated essays.

If you could live anywhere in the world, where would you live?

Oh, that’s really hard! I’d like to go to New Zealand, I’d like to try that out for a bit, I’ve never been before.

What’s your favourite meal?

I’m so faddy with food, so this is really difficult – but I love fish, so I think it would have to be barbecued mackerel with rosemary and lemon, greens … just-cooked spinach and fresh new potatoes with butter and salt and a massive glass of really delicious Pinot Noir.

What was the first album you bought?

It was a Now one, but I don’t remember which number! So one of those, in the 80s. I was also very proud of having bought De La Soul’s album, 3 Feet High and Rising, I remember playing that at my grandmother’s and she was a bit upset at some of the language in there – she was shocked that my mum had let me buy it!

If you could meet one person, living or dead, who would that be?

Dead, sadly. I would really love to have met Maya Angelou. I heard an interview recently with her that had been recorded just before her death, and I think she was someone that also had so many interactions with so many other African-American writers, thinkers, people who I am also interested in, but she had captured the essence of what they were saying or bringing, in a way that I would just love to hear, on top of everything that she had to say, all of her thoughts on what it meant to be a black woman living a rich, purposeful life.

WoW….

Fantastic you….how far you’ve come….

This is a journey from 1957 you can be extremely proud of this journey … So many achievements…and more to come by the sounds of this.

Congrats!!